During spring and summer, adult birds find mates, build nests, lay eggs, and raise their young. If we’re fortunate enough, we can carefully observe some or all of these activities, sometimes at close range. American Robins, for instance, are known for setting up household in a decorative wreath hanging on someone’s front door, causing human families to resort to using the backdoor for a month or so. Here we’ll describe the nesting habits of three birds common to the Chicago area that have very different styles and skills in nest building.

Bank Swallows

Most visitors to Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary during breeding season will have seen the many acrobatic swallows the area boasts. One species in particular has its nests out in the open for all to see – or at least the entrance to their nests. Bank Swallows build their nests in sand banks, and at Montrose there is a protected section of sand bank that contains an estimated 150 nests of these colonial nesters. The swallows return to this site year after year, refurbishing and reusing nest holes from previous years. If an unmated male Bank Swallow is looking to attract a mate, he will begin digging out a burrow and then fly around its entrance, singing, to attract a female. If a female is interested and chooses him as her mate, both the male and female will work steadily, using their small conical bills, feet, and wings to remove earth, progressing about 5 inches per day. As they dig further into the bank, they kick out dirt from the burrow. These tunnels range from 10 to 60 inches in length; the average length is 28 inches. The end of the tunnel is where the pair deposit plant stalks, grass stems, and similar nesting material, and eventually the female deposits 4 to 6 eggs. Once incubation has started, feathers are added to the nest. Incubation is managed by both parents, as is feeding. Chicks are fed flying insects caught by the parents, carrying them back through the tunnel to the nest. As the chicks get older, they will come to the opening of the tunnel to be fed.

Bank Swallow, Montrose Point Bird Sanctuary, Chicago, Illinois

Adam Pershan/Audubon Photography Awards

We are fortunate in Chicago to be able to observe Bank Swallow nests so closely at Montrose, but other locations that have served as nest sites include gravel pits, road cuts, and sand quarries. These human-developed sites have created habitats for Bank Swallows but are also subject to destruction; thus they are not ideal as long-term nesting sites. Over 90% of Bank Swallows of one colony nested within 6 miles of their natal site, or last-year’s nesting site, which points to the need for protection of long-term natural sites. Overall, Bank Swallows have declined by over 5% per year between 1966 and 2014, resulting in a cumulative decline of 94%, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey.

Chimney Swifts

Chimney Swifts are well known in the Chicago area. The ubiquitous chattering birds seem to fly constantly once they’ve migrated here from South America in the spring. These insectivores can fly up to 500 miles in a day to consume at least 1,000 insects, but where do they rest? And nest?

As their name suggests, they roost in chimneys. Before chimneys were built in North America, they roosted in tree cavities, and in rural areas that may still occur. Most, however, use chimneys, silos, air shafts and other narrow vertical surfaces, ideally made of brick, stone, or other material that has rough texture. Why? Because Chimney Swifts do not perch – they cling. Their small, strong feet are tipped with four claws used to hold on to the vertical surface. In addition, the tail feather shafts have exposed spines that provide support for clinging.

Chimney Swifts typically roost together in large numbers in a single shaft. However, nesting birds do not share sites with other pairs. Although there might be unmated swifts sharing a chimney with a breeding pair – and one or two might actually help out the pair – each breeding pair requires a site of its own to nest. Nest building by birds who never land anywhere except in a semi-enclosed vertical surface is done via their aerial skills. Although early documentation stated that parents break off twigs from the ends of dead branches with their feet and then transfer the twigs to their bill – all while flying! – photographic evidence indicates that swifts use only their bill to break off twigs. The twigs are brought back to the nest site, where they are glued together and to the wall of the chimney by the bird’s saliva from a gland under its tongue, forming a shallow cup about 4 inches across. It takes about 3 to 6 days to build the nest. Typically there are 4 to 5 eggs laid, incubated by both parents and sometimes by a helper. The parents and helpers feed the chicks insects caught on the fly, catching up to 12,000 a day when feeding youngsters. The young climb up the chimney, clinging to it, at 19 days old and leave it completely at around 28 days. Swift pairs tend to return to the same nesting chimney every year.

The nest of a Chimney Swift.

https://www.birdscanada.org/bird-science/swiftwatch

Despite the seeming presence of a wealth of ready-made homes for Chimney Swifts, their numbers are in decline. As with other aerial insectivores, the loss of insect populations that provide food for swifts is partially to blame, but changes to how chimneys are built are also a factor. Chimneys best suited for swifts haven’t been built since the 1960s. Traditional brick chimneys, unless maintained, are deteriorating, and many are capped as they are no longer in use. Modern chimneys such as metal ones tend to be unsuitable for nest sites. But you can build your own Chimney Swift tower for roosting or nesting birds, given a suitable site and necessary skills.

Volunteer monitoring a Chimney Swift tower, USFWS, Public Domain. https://www.fws.gov/media/volunteer-monitoring-chimney-swift-tower

Mourning Doves

Not all birds are driven to achieve such mastery in nest building as Bank Swallows or Chimney Swifts. The Mourning Dove is notorious for ill-planned nest locations and seemingly halfhearted nest construction. There is a Reddit community devoted to documenting locations and nest building skills of Mourning Doves. Some popular nest locations include car windshield wiper wells, the tops of window air conditioners, the tops of porch lights and porch ceiling fans, roof gutters, potted plants, and sometimes on the ground. In a more natural setting, Mourning Doves nest in trees or shrubs; however, the basic nest – an assembly of twigs, often without a lining – is typically described as appearing fragile and almost transparent, regardless of the location.

Mourning Dove, adult female and nestling in a Geranium sp. hanging basket, Genesee county, Michigan.

Susan Gardner/Audubon Photography Awards

Mated Mourning Doves build the nest together, yet the methodology and division of labor may explain why abundant nest material often appears scattered below the actual nest. The female dove sits on a nest site of her choosing while the male goes off to find small twigs, which he then presents to her while standing on her back! She accepts the twig and then weaves it around her body, ideally forming a small bowl. However, as mentioned earlier, not all nests attain such a shape or sturdiness.

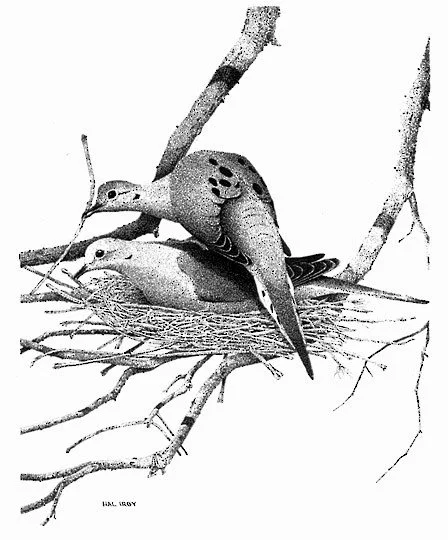

Male Mourning Dove stands on the female’s back while presenting nesting material.

Illustration by Harold D. Irby. https://birdsoftheworld-org.proxy.birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/moudov/cur/breeding

The female lays two eggs which are incubated by both parents, with the female taking the duty during the night, the male during the day. There are typically 2 to 3 broods. Mourning Doves are seed eaters, but what they feed their young for the first few days is called “crop milk”, a cheesy product of the dove’s crop that is high in fat and protein. The crop milk is regurgitated into the nestlings' mouths, as are seeds as the babies grow older.

Unlike Bank Swallows and Chimney Swifts, the Mourning Dove population in the U.S. is robust, with estimated population totals ranging from 350 to 475 million. In turn, the Mourning Dove is the most hunted migratory game bird in North America, and dove hunting is a popular sport in 38 states, including Illinois. Our urban Mourning Doves are safe from hunting by humans, but adults and young are preyed on by raptors, racoons, and cats. Just a reminder – keep your cats inside!

Wherever you may find a nest of any kind, please be respectful of the eggs or chicks inside, and of the parents who are likely fretting nearby. Almost all eggs and nests are federally protected. Please follow these guidelines if you encounter a nest.

Sources:

https://www.swallowconservation.org/bank-swallows

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Bank_Swallow/lifehistory

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Chimney_Swift/overview

https://www.fws.gov/story/chimney-swifts

https://dnr.maryland.gov/wildlife/pages/plants_wildlife/chimswtower.aspx

https://birdsoftheworld-org.proxy.birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/chiswi/cur/introduction

https://birdsoftheworld-org.proxy.birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/moudov/cur/introduction

https://www.fws.gov/story/2021-12/information-dove-hunters

Baicich, Paul J. and Colin J.O. Harrison. A guide to the nests, eggs, and nestlings of North American birds. 2nd ed., San Diego, Academic Press, 1997.

Harrison, Hal H. A field guide to birds’ nests of 285 species found breeding in the United States east of the Mississippi River. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975.